Have you ever been watching a thunderstorm and witnessed someone counting the seconds between the lightning and the thunder (or even counted yourself)? You probably know that you can determine how far away the lightning strike was from the length of time between the lightning flash and the thunder clap. The general approximation is that 5 seconds between the lightning and thunder means the lightning strike was 1 mile away, 10 seconds means the lightning was 2 miles away, and so on and so forth. But you probably know that already.

Did you know that you can take that measurement a few steps further and relate the duration of the thunder roll to the length of the lightning channel? It’s the same idea as determining how far away the lightning strike was, but the physics are slightly more involved.

A Very Simple Example

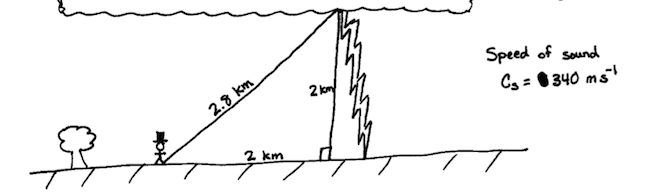

Consider a very simple model of a cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning strike 2 km away. The lightning channel comes straight down out of the cloud and the ground is flat (I apologize for my lousy art skills that make it look otherwise). The cloud base is 2 km above the ground.

We can use speed equals distance over time to uncover plenty of information about the thunder. Since we have a right triangle, we can use the Pythagorean Theorem to determing that you are 2.8 km from where the lightning channel comes out of the bottom of the cloud.

You will hear the top of the strike at:

![]()

The duration of the thunder roll is simply the time difference between when the top and the bottom of the strike reach your ear.

![]()

Since we can measure the duration of the thunder much easier than we can measure the length of the lightning channel, we can work backwards to determine the length of the lightning channel and how far away the strike is. Note that in the real world, the lightning channel is never straight, so these calculations will be for minimum values.

A Simple Real-World Example

Assume a straight-line propagation of the sound wave from thunder at a speed of 340 m/s (the speed of sound). In other words, the sound wave comes straight from the lightning to your ear and does not go up hills, around corners, or anything like that. An observer hears thunder 10 seconds after seeing a lightning flash, and the thunder lasts for 8 seconds.

How far is the observer from the closest point on the lightning channel?

The sound from the closest point on the lightning channel reaches your ear first, which occurs 10 seconds after you see the lightning flash.

![]()

What is the minimum length of the flash?

The minimum length of the channel would be if the channel were a straight line. In the real world, lightning channels are never straight lines, but can get pretty close. At least close enough to validate this approximation.

![]()

Under what circumstances would the length calculated in the previous part be the actual length of the lightning channel?

For the minimum length to be the actual length of the lightning channel, you want the sound from each end of the lightning channel to travel the same path to your ear. Remember that the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. The explanation is quite complicated and involves much more complicated math, which I don’t want to get into and I’m sure you don’t want to hear about, so you’ll just have to take my word for it.

Anyway, if the sound from each end of the lightning channel travels the same path to your ear, you are perfectly in line with the channel. If you take a piece of pipe and look through it like a telescope, that is what being perfectly in line with the pipe is. The light coming into the end of the pipe travels to your eye in the same path as the light inside the pipe. Otherwise you’d be seeing all sorts of different images. Unfortunately, if you’re dealing with a cloud-to-ground strike, being perfectly in line with the lightning channel means that you are being struck by it, so I really wouldn’t recommend trying to experience that.

So that’s a few cool new tricks you can do with the next thunderstorm you see. At worst, it’ll explain why the long rolls of thunder come from cloud-to-cloud strikes (which can reach lengths greater than 20 km), but hopefully it’ll help you understand a little bit more of what’s going on inside that thunderhead.