Dual polarization radar is an incredibly powerful tool for tracking severe weather. One important use for dual-pol radar is to track strong tornadoes by detecting the debris field with the radar. Similar to the Moore tornado last year, the April 27, 2014 Vilonia, Arkansas tornado passed about 10 miles north and west the radar site, providing about as good a low-level scan of the tornado as possible.

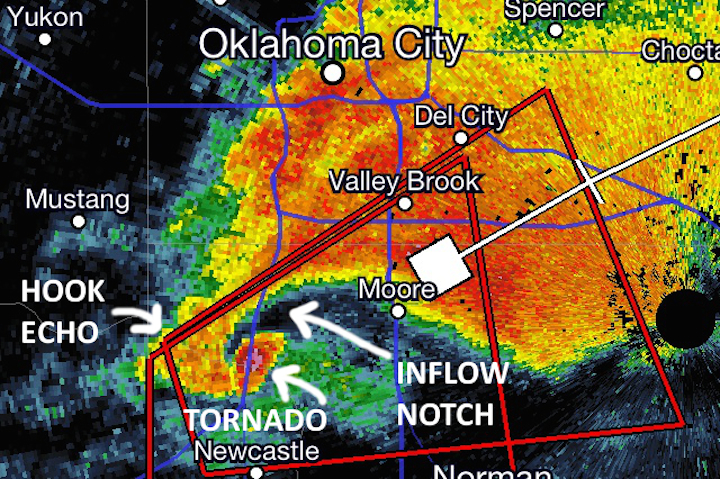

First, let’s recall what a classic supercell looks like on radar. The area of greatest interest is the hook echo and tornado, located near the back of the storm. Remember that when a tornado picks up debris and throws it in the air, it has a high reflectivity (the radar beam bounces off of it very easily), and shows up in the scan below as purple and pink. The scan is from last year’s Moore tornado.

Radar Image of Classic Supercell — May 20, 2013 Moore, OK Tornado

When we look at the reflectivity scan of a tornadic supercell, we want to look for three features: the hook echo, the tornado, and the inflow notch. The hook echo and tornado can sometimes be hard to see on the radar scan, locating the inflow notch is an easy way to locate a possible tornado. The inflow notch, which appears on radar as an area of no precipitation ahead of the tornado (black on the above scan), is the air from the surface being sucked into the tornado. On many storms, the inflow notch looks like someone took a bite out of the side of the storm. I do want to emphasize that all an inflow notch means is that the storm is rotating. It does not indicate whether or not a tornado is on the ground. If there is a tornado, it will be just to the south/west of the inflow notch. In fact, reflectivity alone cannot 100 percent confirm a tornado is on the ground.

We will look at four different radar parameters to determine if a tornado is present. We will look at reflectivity and velocity (wind speed and direction), as well as the correlation coefficient and differential reflectivity, which are dual-pol variables that indicate the shape of the object the radar is detecting. Any one of these scan by themselves cannot confirm for certain that a tornado is on the ground, but with all four together, you can say with near 100% certainty that a tornado is on the ground.

Now, let’s have a look at the Vilonia tornado, starting with the reflectivity on the left below. If you’re not well-versed in radar, the hook echo may be a little hard to detect, so I have indicated the location of the inflow notch. The tornado is the pink dot just southwest of the inflow notch.

On the right is the velocity scan. Because of the way radars work, it can only detect motion going towards it (shown as green on the scan) or away from it (shown as red on the scan) and cannot detect side-to-side motion, but since tornadoes rotate, two wind vectors somewhere in the tornado are always aligned perfectly with the radar beam (one towards it and one away from it), providing a full reading of the wind speed vector. The brighter the color is, the stronger the wind is, but do note that the brightest reds show up as orange on this particular scan. To locate the tornado, look for a small and really bright red spot right next to a small and really bright green spot. This is called a couplet, and indicates a small area of really strong winds going in one direction right next to a small area of really strong winds going in the opposite direction, or to put it simply, that the storm is rapidly rotating. The couplet is circled in the velocity scan below. The darkest orange/brown color indicates wind speeds close to 140 mph!

Reflectivity Scan – Vilonia, Arkansas Tornado

Velocity Scan – Vilonia, Arkansas Tornado

So far we have show that the storm has an area of very strong rotation in the hook echo of a supercell, and that area of rotation has a very high reflectivity. This is enough to say with 90-95 percent certainty that there is a tornado, but not with complete 100 percent certainty. To do that, we must look at the dual pol data. The best dual pol variable to look at is the correlation coefficient. I’m not going to go into the math behind it, but the definition of the correlation coefficient is the measure (ratio) of how similarly the horizontally and vertically polarized pulses are behaving within a pulse volume. Its values range from 0 to 1. For example, if a perfectly spherical object is being detected, the horizontal and vertical pulses will be the same, so when you divide one by the other, you will get 1. Correlation coefficients for rain are generally above 0.95, and are typically above above 0.85 for hail. On the other hand, if the radar is detecting a tree limb or a 2×4 flying around, they are nowhere close to being spherical, so their correlation coefficients will be much lower — 0.3 to 0.4 at the highest. If there is a debris cloud around the tornado, correlation coefficients will be low (less than 0.5 or 0.6) in the same spot the area of intense rotation is on the velocity scans. Low correlation coefficients are indicated by dark blue and black colors.

Differential reflectivity is the difference in returned energy (reflectivity) between the horizontal and vertical pulses of the radar, and is similar to the correlation coefficient. Since reflectivity is a logarithmic scale, this becomes a ratio of the horizontal reflectivity to the vertical reflectivity. Differential reflectivity values from a tornado’s debris field will also be very low, and can be seen in gray and black in the scan below.

Correlation Coefficient – Vilonia, Arkansas Tornado

Differential Reflectivity – Vilonia, Arkansas Tornado

Now, we have determined we have an area of very intense rotation in the hook echo of a supercell and there are objects with very low correlation coefficients and differential reflectivity values in the same location as area of intense rotation, indicating that very non-spherical objects are being detected about 600 feet in the air and a debris field is present. The presence of a debris field allows us to say with 100 percent certainty that a tornado is on the ground and likely doing damage.