There are 7 essential elements to deeply engage and grip your audience as you tell your story. Regardless of what type of media you’re using to tell your story, these essential elements will help leave your audience at the edge of their seats, craving to come back and see what happens next.

Today, we’ll be using these essential story elements to tell the story of the EF-5 tornado that struck Moore, Oklahoma on 20 May, 2013. Even though we’ll be using maps and photography to tell the story, you could easily use a video, blog post, podcast, and much more, too.

Plan As Many Story Elements as You Can

It’s hard to tell a story if you don’t know the basic elements. As a result, you should plan out as many elements of your story as possible. If you’re planning a photo and video shoot, these elements of your story don’t need to be set in stone – there’s a lot if improvising in making travel videos, for example, especially if you’re going to be shooting in a location you’ve never been to before.

But you should have at least a general idea of how you’ll portray your story to your readers. Without that planning, you’ll likely miss shots while you’re out filming, and negatively impact the quality of your final presentation. Simply do your research and plan out your story before you go out on a photo or video shoot. This technique works, even for difficult-to-plan genres, such as travel videos.

1. Set the Stage in the Setting

At the beginning of your story, you have a very limited time to set the stage for your story. With video, you you need to both set the stage and hook your viewer in the first 10-15 seconds.

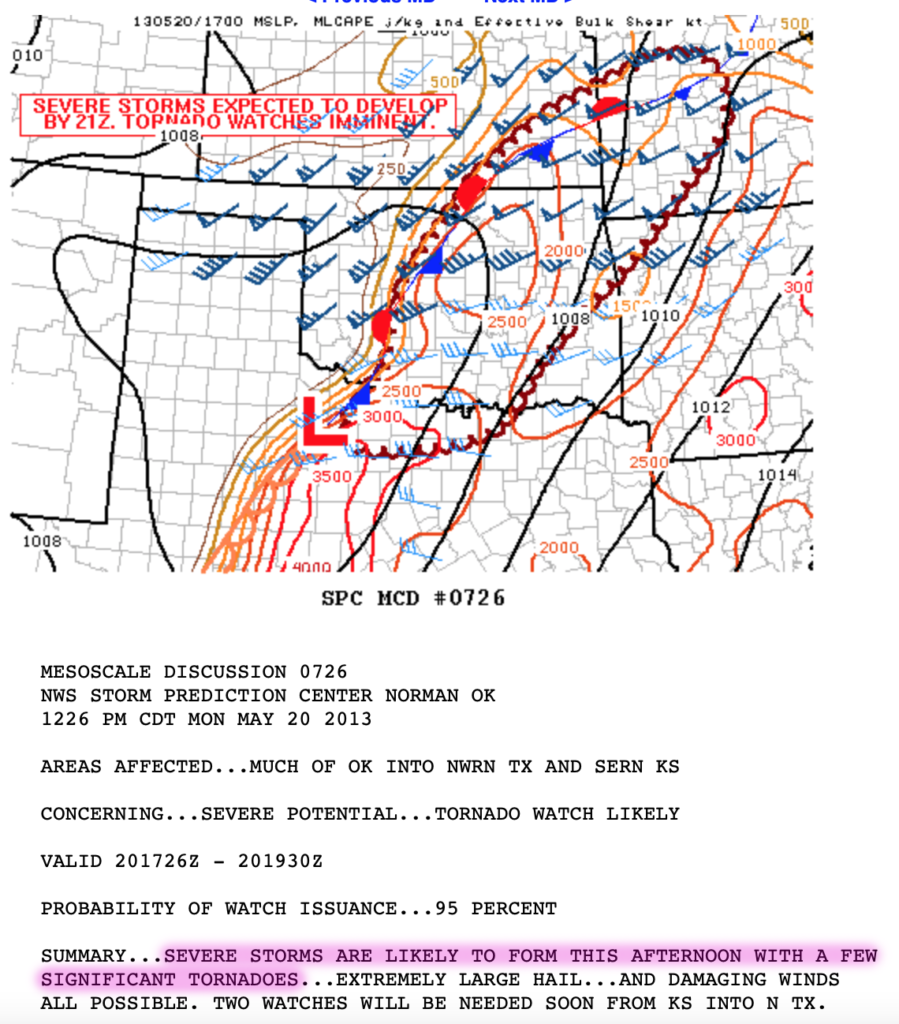

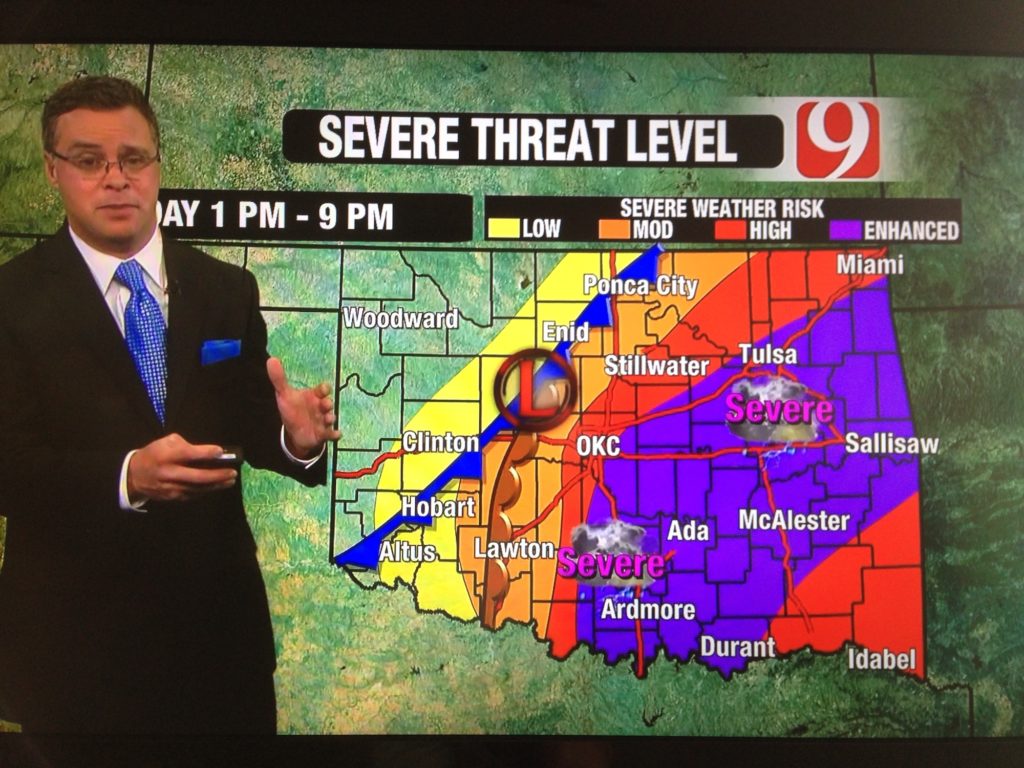

For the Moore tornado, the stage will be set on the morning of 20 May. It’s the third, and most dangerous day of a three-day tornado outbreak across the southern plains. The previous day had seen violent tornadoes in Oklahoma, including an EF-4 inside the Oklahoma City metro that carved a path from Norman to Shawnee. We’ll use the Day 1 SPC outlooks and discussions to set the stage (note the usage of the strong, long-track tornadoes wording), as well as storm reports from the 19th. Furthermore, when you stepped outside that morning, it just had “that felling” that something significant was about to happen.

2. Determine the Point of View From Which Your Story is Told

From whose point of view will you be telling your story? Consider a murder mystery. The story will have a very different feel being told from the murderer’s point of view vs the detectives’ point of view.

For an event like the Moore tornado, you could choose to tell it through the point of view of the news media. While there is nothing wrong with this approach, there is a much better way to tell the story. And that’s through the eyes of someone who was there when it happened. As a result, I’ll be sharing my firsthand account of my experience that day.

3. Introduce Your Characters

Before you begin telling your story, you should at the very least know who the main characters are. For the Moore tornado (and some of my travel videos), I am the main character. On the other hand, if you’re telling the story of a place or event with historical significance, you’ll need to transport your audience back in time. The people who lived through those historical events will be your main characters. But to fully immerse your audience in your story, try making them the main character. Tell your story in second person, and let your audience experience it.

If you’re planning the story of something that can’t be scripted – like travel videos or blogs – it’s perfectly okay to not know every single character. When you’re traveling, you never know the interesting people with colorful personalities you’ll meet along the way. This could be a random stranger you’re sitting next to at lunch or on the train. Maybe it’s the proprietor of an incredible hole-in-the-wall coffee shop you stopped at along the way. Or perhaps, it’s the local guide that you hired for that bucket-list experience. Once you get done filming your adventure, just make sure you know how every character works into your story. And if they don’t play a meaningful role in moving your story along, leave them out.

4. Every Story Needs a Hook

The hook is one of the most important elements of your story, if not the most important. As you set the stage for your story, you also need to dangle a “hook” to your reader or viewer. That hook is designed to draw them into the story. It shouldn’t leave them just yearning to see what happens next. It should leave them craving it. Have you ever binge-watched a show all at once? The writers of bingeable shows are incredibly gifted at creating effective hooks. Those hooks are what keeps you pushing forward to the next episode instead of turning off the TV and going to do something else.

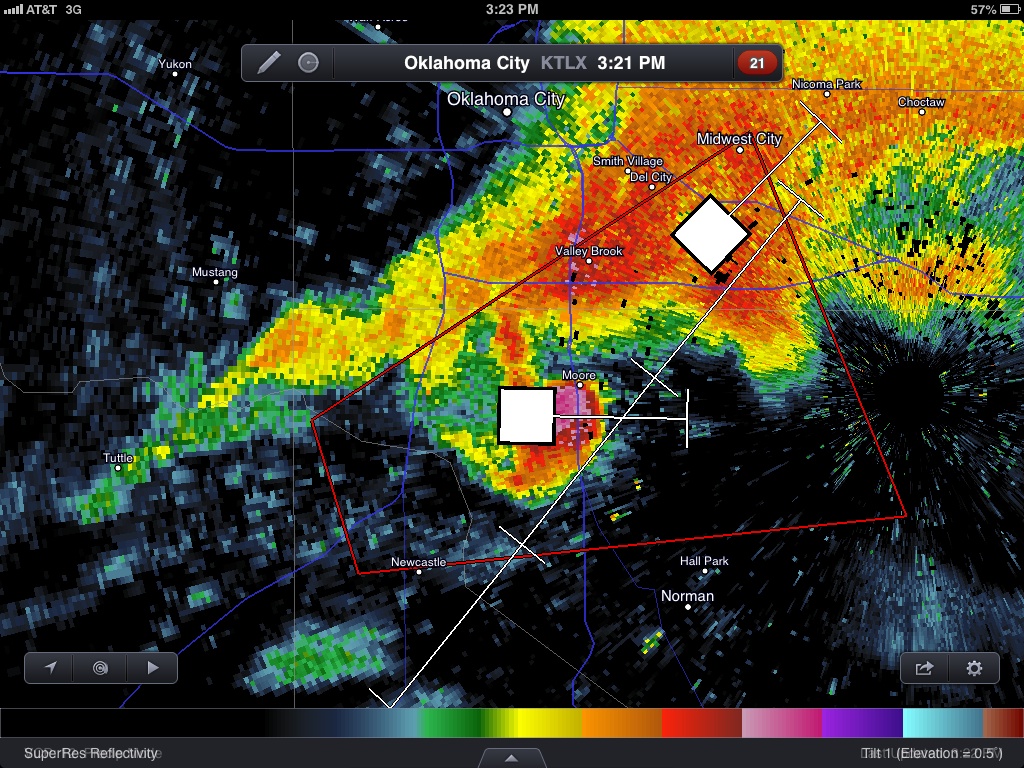

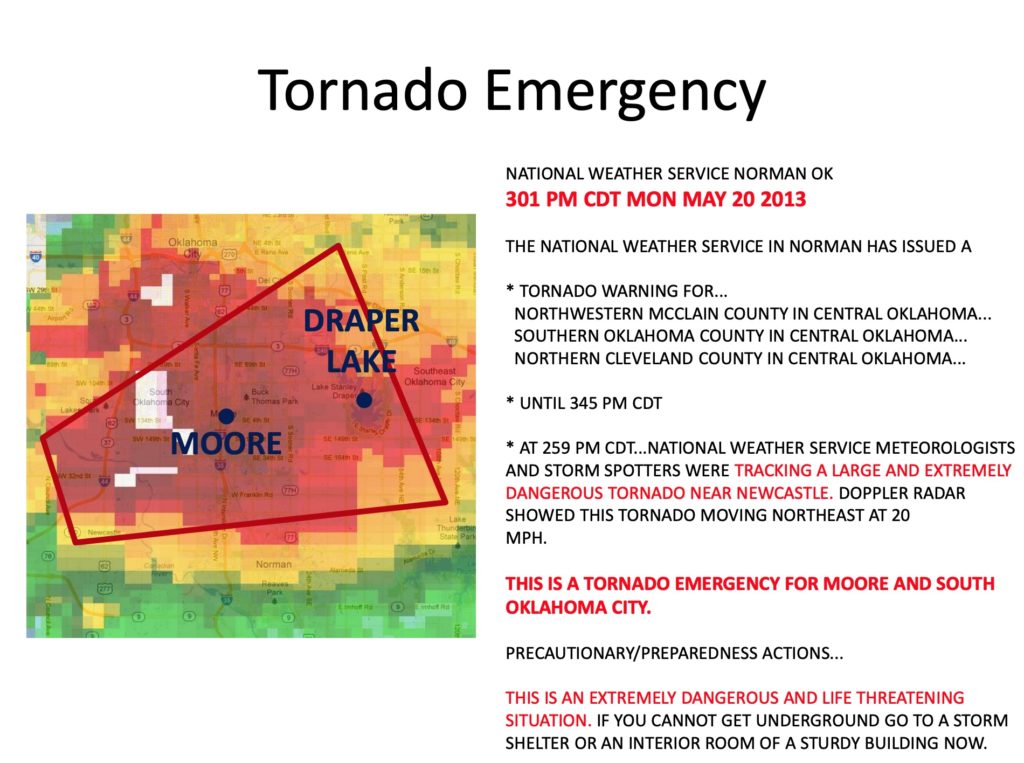

A good hook gives a sneak peak of what’s coming, but doesn’t give the storyline away. It could be a review of the conflict, the resolution, or anything else in the story. For the Moore tornado, we can state what the tornado hit – two elementary schools and a hospital. Notice that we didn’t say how much damage was done or if there were any injuries or causalities. We could also show the radar and the tornado emergency that was issued for the City of Moore as the tornado barreled towards it.

5. The Plot

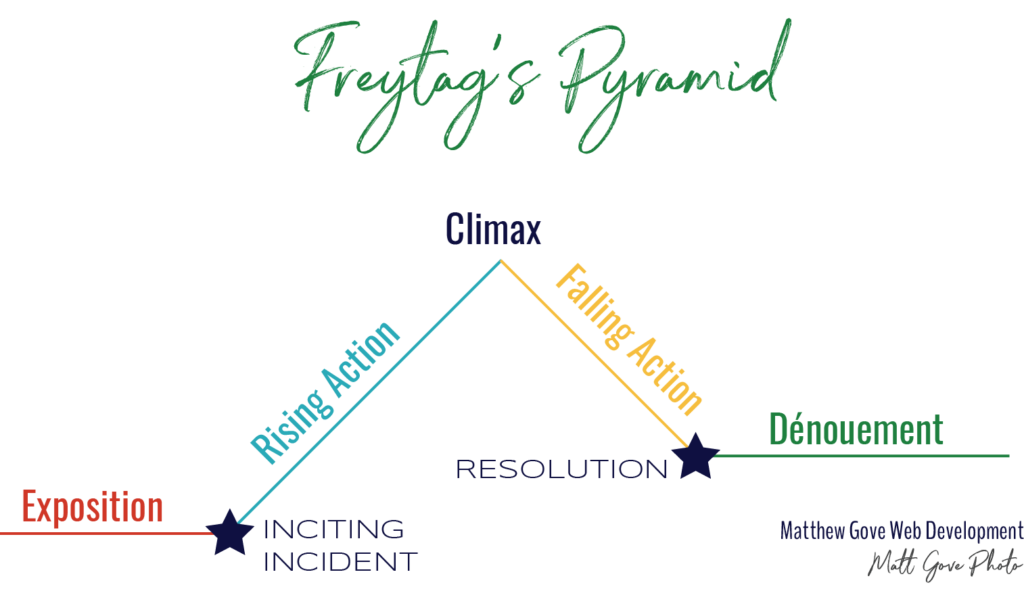

The plot is the most important of all story elements, by far. In fact, I could write an entire post (and I probably will) on how to structure your plot to keep your readers engaged and wanting to know what will happen next. Plots are broken into 5 elements, and we can use a Freytag’s Pyramid to illustrate those 5 stages.

Plot Elements for Your Story

- Exposition. Set the stage for your story. Introduce your characters, give your audience the hook to draw them in, and begin to introduce the primary conflict.

- Rising Action. In this stage, your protagonist addresses the primary conflict with a form of action. As you approach the climax, those actions should build and escalate tension, like approaching the top of a roller coaster.

- Climax. This is the pivotal moment your audience has been waiting for. Your protagonist will encounter their greatest challenge of the entire journey. It’s the culmination of the buildup of tension during the rising action phase. Make it exciting for your audience!

- Falling Action. Your protagonist will deal with the consequences and fallout – both good and bad – of everything that happened during the climax. Keep your audience engaged by setting the stage for the story’s conclusion. By the end of this phase, you’ll be well on your way to a (hopefully satisfying) conclusion. Additionally, you should start resolving any conflicts that arose as a result of the climax.

- Resolution or Dénouement. You can go one of two ways here. If this is actually the end of your story, wrap everything up. Tie up loose ends. Give your audience a sense of closure so they know the fate of your protagonist. On the other hand, if you’re writing a series or sequel, you should introduce another hook to leave your audience craving the next episode. Cliffhangers work exceptionally well as that hook.

Now, let’s look at how we can apply Freytag’s Pyramid to the plot of the story of the Moore tornado.

The Plot Elements of the Moore Tornado

| Element | Moore Tornado Plot |

|---|---|

| Exposition | Summary of first two days of tornado outbreak; SPC Outlook Maps highlighting the extremely dangerous conditions on 20 May |

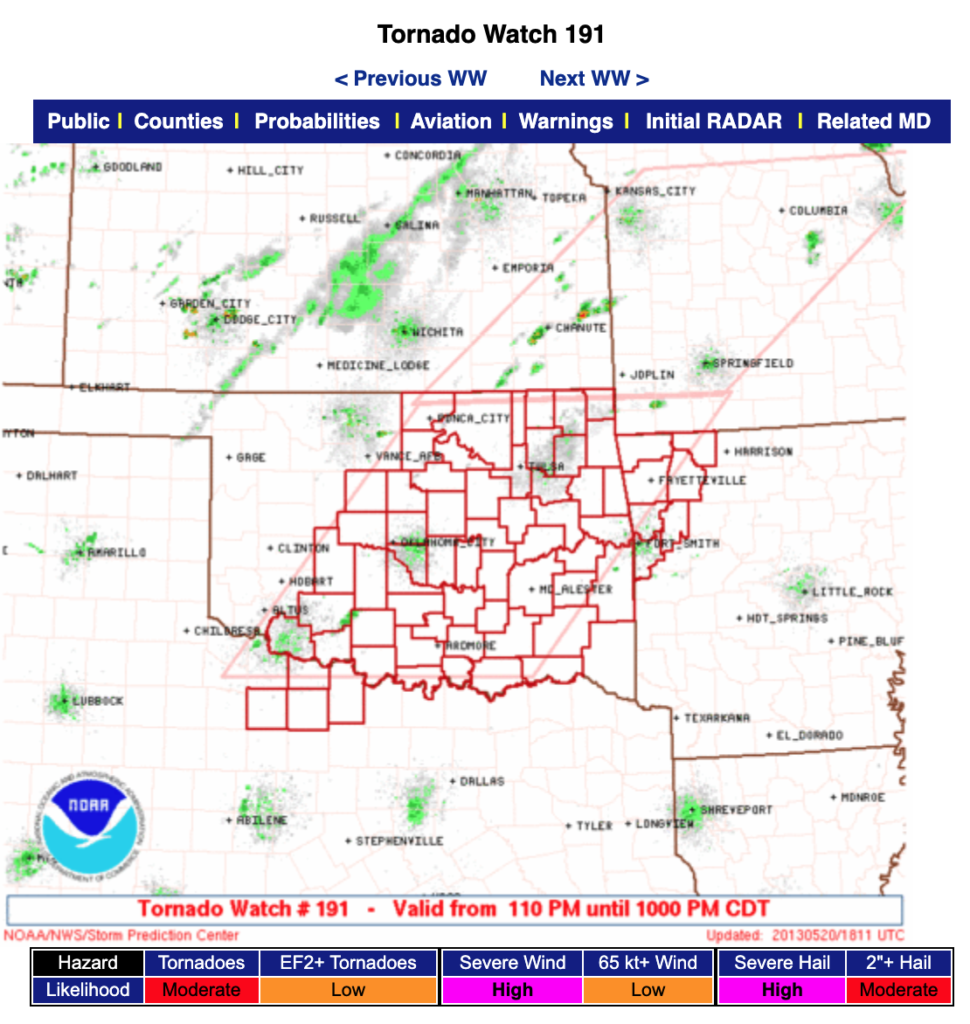

| Rising Action | Statements from the National Weather Service with stronger wording as the day goes on. Culminates with a Particularly Dangerous Situation Tornado Watch for Central Oklahoma |

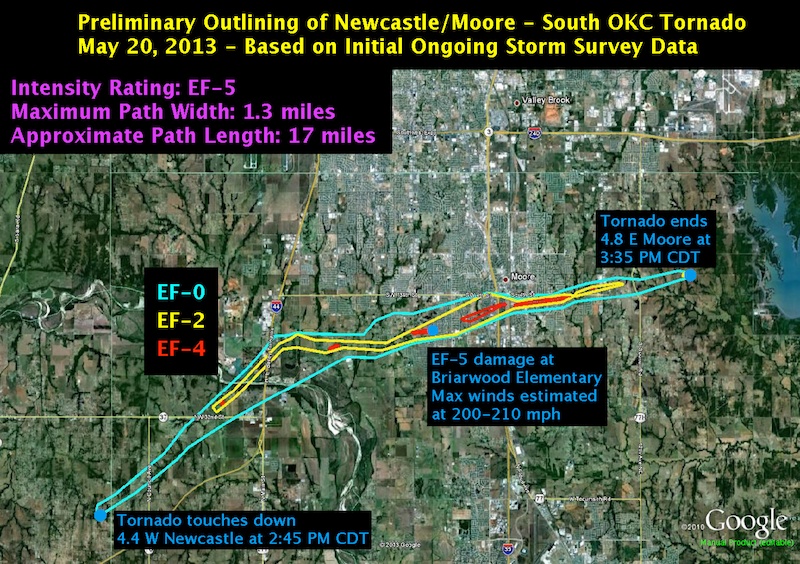

| Climax | The tornado touches down southwest of Moore. The National Weather Service issues a Tornado Emergency issued almost immediately. The tornado tears a 17-mile path through the guts of Moore, packing peak winds of 210 mph (338 km/h). It makes a direct hit on two elementary schools and a hospital. |

| Falling Action | Starts with the search and rescue efforts in the immediate aftermath of the tornado. The federal government declares Moore a major disaster area. Once critical infrastructure is restored, residents are let back in, but the looters come in too. Then the long cleanup and recovery process can begin. The outpouring of support from all over the world is incredible. The tornado ultimately kills 24 people, including 7 children at Plaza Towers Elementary School. |

| Resolution | Moore one year later. Neighborhoods in the damage path have largely been rebuilt, and the two destroyed elementary schools are slated to re-open in the fall. The lack of trees in a once lush neighborhood serves as a constant reminder of the tornado’s destruction. |

6. Without a Conflict, There is No Story

Your story’s conflict answers the question of why your character is embarking on this journey. Without a conflict, you don’t have a story. It’s as simple as that. In your story, the conflict is what causes your character to take action and move the story forward. Conflicts can be both physical and mental. For example, if you’re telling a story about climbing Mt. Everest, the physical or external conflict consists of all the dangers your character encounters on their way to the summit. From frigid temperatures to thin air to dangerous terrain to altitude sickness, one false move could kill your character as they ascend the mountain.

On the other hand, let’s look at a mental conflict. Mental conflicts are internal journeys, and often tend to focus on a single main character. The best example of a simple mental conflict is a character’s journey to overcome their fear of heights so they can go skydiving or bungee jumping. You could also tell the story of how your protagonist overcame their stutter to become a great public speaker.

Keep in mind that while there is usually only one primary conflict, most stories have multiple conflicts. Additional conflicts tend to come in two forms. First, they can be sub-conflicts, that when put together, make up the primary conflict. If you’ve ever seen Monty Python and the Holy Grail, King Arthur’s quest to find the grail is comprised of numerous smaller conflicts they encounter along the way. The conflicts escalate as they get closer to the grail, culminating with the Bridge of Death and the Killer Bunny.

Cascading Conflicts in the Aftermath of the Moore Tornado

Conflicts in the story of the Moore Tornado fall into the second category of multiple conflicts. In these stories, the primary conflict sets off a series of additional conflicts during the falling action. In Moore, the primary conflict is the tornado itself. But after the tornado levels the city, a whole new slate of smaller conflicts emerges.

- With the city’s critical infrastructure destroyed, how do search and rescue teams coordinate and communicate their efforts?

- Debris is everywhere, rendering roads impassable. How do search and rescue teams get into these areas and rescue survivors without using the roads?

- The damage path is 17 miles long and 1 mile wide. Where do search and rescue teams, as well as city and state resources, prioritize their efforts?

- What do survivors do and where do we send them once they’re rescued? How do we get relief to storm victims as soon as possible?

There are obviously many more conflicts than just this following a major tornado, but this should get you started.

Even the Simplest Stories Have Conflicts

When you tell your story, remember that you can find conflict in even the simplest, most monotonous things. Take going to the grocery store as an example. I can think of one major conflict we’ve encountered going to the grocery store recently: the COVID-19 pandemic.

But even without a global pandemic, you can still find conflict to tell the story of your trip to the grocery store. Maybe you’re looking for a very special ingredient and have to go to 3 or 4 stores before you find it. Perhaps your character has fallen on hard times and needs to stretch a tight budget as far as possible. Or what if there’s a major winter storm coming and you have to fight through treacherous conditions and low supply to stock up ahead of the storm.

Conflicts can be really anything you think of, but you need to know your audience. If you create a story that your audience isn’t interested in, they’re not going to listen to you tell it. If you’re stuck looking for a conflict, ask yourself why your character is going on this journey. The answer to that question is the conflict in your story.

7. The Resolution

At the end of your story, you should tie up all loose ends and give your audience a sense of closure for how your story ended. Regardless of whether your story has a happy or sad ending, your audience should know what the characters’ lives will look like now that their struggles are over and the conflict has been resolved.

However, if you’re planning on writing a sequel or another episode, you can easily leave the door open to another chapter of the story. While one conflict is resolved, your character may facing another one. In that case, dangle another hook or cliffhanger to leave your audience eagerly waiting to come back for the next chapter. Then you can go back to the beginning of this guide and start the journey all over again.

The Moore Tornado Story in Maps and Pictures

Conclusion

Regardless of what media you are using to tell your story, you’ll be using the same seven elements to tell it. Planning is critical to being able to tell an insightful and engaging story, especially if you have to go out and shoot photos or video of it. Without a plan, your story will wander and ramble, and your audience will lose interest. Set the stage, hook them in, and leave them craving to see what happens next. Because at the end of the day, you shouldn’t want to just tell your story. You should want your audience to experience it.

Top Photo: The Reward at the End of a Tough Hike

Sedona, Arizona – August, 2016