As a former storm chaser, weather and meteorology have greatly influenced my career, values, and philosophy. Nowhere is that more true than in my photography. Even though I was only a hobbyist photographer at the time, storm chasing was clearly the turning moment when I realized my photography skills were good enough to be able to do professionally. To this day, weather forecasting models remain the secret weapon I use to set my landscape photography apart from the competition. And now, I want to share some of that knowledge with you.

Why Is Weather Forecasting Important for Landscape Photography?

Anyone can go out and take pictures of a beautiful landscape. We all have cameras on our smartphones these days. But what separates your “Average Joe” tourist from a world-renown National Geographic photographer? It’s a long list, but one of the primary reasons is that most tourists don’t take weather into consideration. They just shoot.

In the worst-case scenario, bad weather will ruin a photo op. At best, you’re missing out on an incredible opportunity. In most landscape photos, the sky takes up at least one third of the frame. That’s a lot of wasted real estate. On the other hand, use weather to your advantage and instantly set yourself apart from the bulk of the competition.

But just hoping you’ll get lucky with the weather is not enough. Getting the right weather for your shot is a crapshoot at the best of times. Without a strategy, you’re setting yourself up for a low success rate and an inefficient workflow. However, when armed with basic knowledge of weather models, you’ll be able to target your photo shoots with laser-like precision. The frustration will be gone, and you can enjoy much more efficiency and success.

Being Flexible and Adaptable is Key to Your Success in Weather Forecasting for Landscape Photography

Let’s say you get up in the morning hoping to get a good sunset picture later in the day. After a quick look at the models, you identify a precise location with ideal conditions for sunset photos. Even better, it overlaps with the evening Golden Hour. As you go through the day, model runs start showing a significant increase in thick, low-level clouds in the evening. Instead of giving up, toss your planned sunset shoot out the window. You pick a new location and shoot some breathtaking black-and-whites of dramatic sunlight shining through the thick low-level clouds on the rugged landscape like a spotlight.

Without the help of the weather models, you would have come away with nothing. When integrating weather into my landscape photography, I use the same strategy I did when I was storm chasing.

Applying Storm Chasing Strategy to Landscape Photography

On paper, storm chasing strategy is shockingly simple.

- Look for where and when the ingredients for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes best come together.

- Drive to that target area, arriving shortly before that window of peak potential opens.

- Wait for storms to fire.

- Once storms initiate, go chase them, keeping in mind the important balance of safety vs getting the shot.

Unfortunately, in practice, it’s never that easy. Your window of opportunity will constantly shift in both time and space. Better opportunities will appear elsewhere. Sometimes, those opportunities won’t even manifest, leaving you with the inevitable bust. Things happen incredibly fast when you’re storm chasing, so you need to be quick on your feet and always be able to react to whatever curveballs Mother Nature throws at you.

Thankfully, things don’t happen as fast in the world of landscape photography. Having more time to react means you have a higher likelihood of success. However, you’ll still need to be just as able to react and adjust, because Mother Nature will throw you curveballs. You can easily apply basic storm chasing strategy to landscape photography using different parameters. Instead of looking for where severe storms are most likely to occur, look for where you’ll get the best sunsets, golden hours, fog, etc. We’ll circle back to this in a bit.

Learn to Embrace Failure in Your Landscape Photography

When dealing with the weather, the only thing that’s for certain is uncertainty. Succeeding at storm chasing requires skill, quick thinking, and luck, as most tornadoes are only on the ground for less than 30 seconds. The same goes for lightning photography. If just 5% of your lightning photos come out, you’re doing extraordinarily well.

Rest assured, you will have a far greater success rate integrating weather into your landscape photography. They’ll be absolutely stunning when you get it right. But you must accept that things can and will go wrong. You will have days where you completely bust. Yes, it’s incredibly frustrating when it happens, but it’s part of the game. Always remember that even the best in the business have off days.

My Own Hero to Zero Experience

Over the course of 9 days in 2012, I pulled the ultimate hero to zero move. However, I still managed to get breathtaking photos despite the most epic storm chasing bust I ever experienced. On 19 May, a powerful storm system came off the Rocky Mountains and across the central Great Plains. Everything seemed to be in place for a massive outbreak of tornadoes across southern Nebraska.

I was living in Norman, Oklahoma at the time, and really didn’t want to drive all the way to Nebraska to have to fight the storm chaser crowds. Instead, I searched the models for a target closer to home. Models hinted at a very brief window opening up along the Kansas-Oklahoma border that was very favorable for tornadoes right before sunset. It wasn’t much of a window – only about 15 to 20 minutes, but it was low risk and high reward. I had to take the gamble.

Right on cue, storms were firing just as I crossed the state line from Oklahoma into Kansas. I got on the first storm I could find and hoped for the best. And boy, did that gamble pay off. Over the course of about 25 minutes, that supercell produced nearly a dozen tornadoes. A spectacular EF-3 tornado capped the evening off, creating a dramatic scene with the setting sun behind it.

The Sweetest Weather Forecasting Victory

Now, here’s where that victory gets even sweeter. The target up in Nebraska that looked really juicy at the start of the day completely fell apart. There was not a single tornado up there, while I got to enjoy the show in Kansas all to myself. As I drove back towards Interstate 35 to head home, I passed all kinds of chase vehicles going towards the storm. I knew the storm was already wrapped in rain and had finished producing tornadoes. They were too late.

An Epic Weather Forecasting Bust Leads to a Satisfying Day of Landscape Photography

Eight days later, I was back in the field for another round of storm chasing. This time, western Kansas was the target, and conditions looked very favorable for tornadoes. I ended up driving nearly 300 miles from Norman, and didn’t see much more than a couple fair weather puffy clouds. The capping inversion hadn’t broken. There would be no storms that day. Then I had to drive the same 300 miles home.

After abandoning the storm chase, I was determined to come home with something…anything. I knew the spring wheat harvest takes place in late May in western Oklahoma, so I decided to try to get some photos of the wheat fields in the late afternoon sun and then catch the sunset at Gloss Mountain State Park. If you’ve never seen wheat fields at harvest time, I highly recommend it. You’ll see right away why Katharine Lee Bates used the “amber waves of grain” lyrics in America the Beautiful.

The photos were certainly nothing I’d be rushing out to try to sell to an art gallery, but as an alternative to coming home empty-handed, it was oddly and uniquely very satisfying.

Weather Forecasting Models for Landscape Photography

For landscape photography weather forecasting, I use the same models that I use for my weather analyses and storm chasing. For the greatest success, you’ll want to use a combination of global and regional models over both the short and long term. My goal here is to introduce you to each model so that you know when to use each model, as well as what their strengths and weaknesses are. We’ll dive into model interpretation and analysis in a future post.

What Is Output When the Weather Models Run?

All weather models output their forecasts in four dimensions: latitude, longitude, height, and time. Logic may dictate that the output formats may vary from model to model, but in reality, they generally output the same three formats.

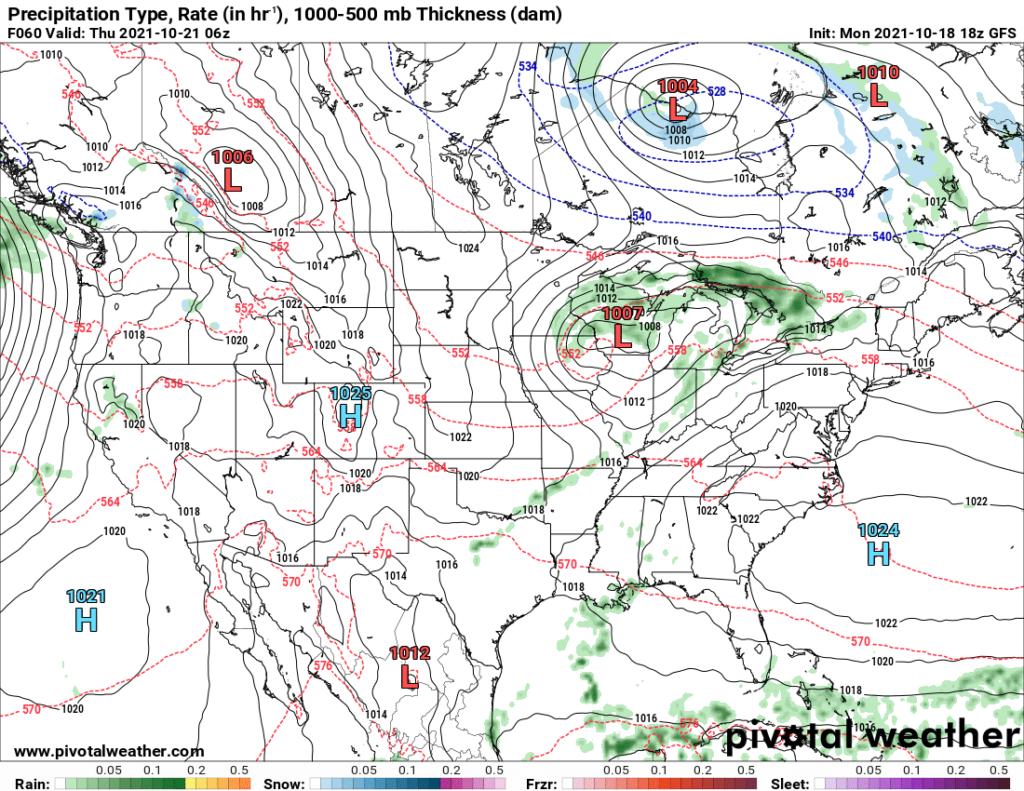

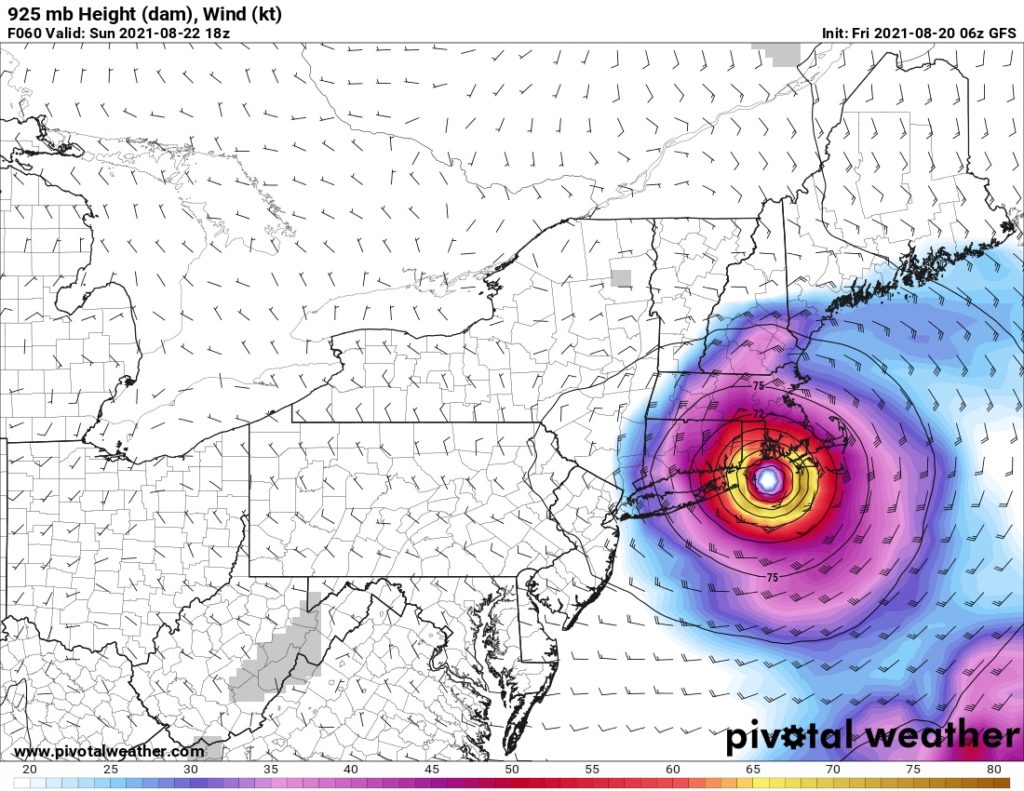

- 2D Geographic Maps

- Vertical Cross-Sections of the Atmosphere

- Time Series Graphs

For basic landscape photography weather forecasting, you can gather all you need from the 2D geographic maps, so these tutorials will focus our efforts on those maps. If you’re interested in learning more, we will cover the other two outputs in future tutorials and online courses.

Global Forecast System (GFS) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | U.S. Federal Government (NOAA) | |

| Runs Per Day | 4 / Every 6 Hours | |

| Spatial Domain | Global | |

| Time Domain | 16 Days, in 3-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 13 km | |

| Best For | Synoptic (Large) Scale Forecasting |

The GFS model is one of the go-to models for general global forecasting. It has received criticism in the past for poor performance, most notably when it predicted that Hurricane Sandy would go harmlessly out to sea. As a result, the model received major upgrades in 2017, 2019, and 2021. While it has performed much better as of late, especially with tropical weather, the GFS has still not fully closed the performance gap with the European model.

European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | European Union | |

| Runs Per Day | 2 / Every 12 Hours | |

| Spatial Domain | Global | |

| Time Domain | 10 Days, in 6-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 9 km | |

| Best For | Synoptic (Large) Scale and Tropical Weather |

The ECMWF model has been around since 1975, but really cemented itself amongst the world’s top weather models when it absolutely nailed its prediction for Hurricane Sandy. Even 10 days out, the ECMWF missed the exact location of Sandy’s landfall by less than 100 km. Today, the ECMWF is still considered to be the most accurate global model, but other models are closing the gap. However, in 2020, ECMWF scientists were awarded time on the world’s most supercomputer to run their model at a 1 km resolution on a global scale. If that can be successful in the long-term, it will be a game changer.

United Kingdom Meteorological Agency (UKMET) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | UK Federal Government | |

| Runs Per Day | 2 / Every 12 Hours | |

| Spatial Domain | Northern Hemisphere | |

| Time Domain | 6 Days, in 6-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 10 km | |

| Best For | Synoptic (Large) Scale and Tropical Weather |

The UKMET model is designed for making medium-range forecasts throughout the entire northern hemisphere. However, it is best known for being used in tropical weather prediction. It is routinely used in tandem with the GFS and the ECMWF when making forecasts.

Global Deterministic Prediction System (GDPS) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | Environment Canada | |

| Runs Per Day | 2 / Every 12 Hours | |

| Spatial Domain | Global | |

| Time Domain | 10 Days, in 6-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 16.7 km | |

| Best For | Synoptic (Large) Scale Forecasting |

Also known as the GEM model, Environment Canada originally created the GDPS model as a comparison or check to the GFS model. While it is now the default weather model that the Government of Canada uses, it can be used interchangeably with or in place of the GFS model.

North American Mesoscale (NAM) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | U.S. Federal Government (NOAA) | |

| Runs Per Day | 4 / Every 6 Hours | |

| Spatial Domain | North America | |

| Time Domain | 84 Hours, in 3-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 12 km | |

| Best For | Severe and Tropical Weather Forecasting |

20 years ago, the NAM was the best model available for storm chasers. While other models have since overtaken it, the NAM is still a very accurate model for significant weather events across North America. It initializes itself with GFS data, so it’s backed by one of the most respected models in the world.

Rapid Refresh (RAP) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | U.S. Federal Government (NOAA) | |

| Runs Per Day | 24 / Every 1 Hour | |

| Spatial Domain | North America | |

| Time Domain | 22 Hours, in 1-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 13 km | |

| Best For | Short-Term Weather Forecasting |

Designed as a fast-updating version of the NAM, the Rapid Refresh model is a favorite amongst storm chasers and hurricane fanatics alike. When using it for storm chasing, it’s one of the most accurate models available today. However, you must keep in mind not to rely too heavily on it. Its 13 km resolution is too coarse to resolve individual thunderstorms.

High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) Model

| Developed and Maintained by | U.S. Federal Government (NOAA) | |

| Runs Per Day | 24 / Every 1 Hour | |

| Spatial Domain | North America | |

| Time Domain | 48 Hours, in 1-Hour Increments | |

| Horizontal Resolution | 3 km | |

| Best For | Short-Term Weather Forecasting |

The HRRR model is the most accurate short-term model available today. I used it all the time for storm chasing, and it never let me down once. Its 3 km resolution if fine enough to resolve nearly every type of weather phenomenon, allowing you to pinpoint precise targets with laser-focused accuracy. In the context of weather forecasting for landscape photography, use it to target sunrises, sunsets, storms, cold fronts, fog/mist, snow, and much more. You can even go beyond Earth’s atmosphere and use it to identify the best nights for astrophotography.

Where to Get Weather Model Output Online

Are you ready to dive into the models and take advantage of weather forecasting to improve your landscape photography? The outputs for all of the models we have covered are readily available online free of charge. While I am in no way affiliated with any of the following organizations, these are my favorite resources for weather models, in no particular order. You can find many more with a quick Google Search.

- Twister Data

- Pivotal Weather

- NOAA NCEP Model Analyses and Guidance

- NOAA: Rapid Refresh and HRRR

- Penn State University E-Wall

General Strategy for Model Analysis and Weather Forecasting

We will dive into model analysis in much greater detail in future tutorials and online courses, but I wanted to at least give you a brief intro. Without knowing how to analyze them, the models are completely worthless. This strategy can be applied to any type of modeling. It’s not limited to just weather forecasting or anything to do with landscape photography.

First and foremost, always use multiple models, regardless of the type of forecasting you’re doing. The more models you have in agreement, the higher the confidence in your forecast will be. Additionally, consider the Hurricane Sandy example. The GFS showed Sandy going harmlessly out to sea. All the other models showed it slamming into the east coast of the United States. Imagine what would have happened if emergency management had been using only the GFS. They would have been caught totally flat footed. Once you have the models selected you want to use, start with the following strategy.

- Look at the current observations and the synoptic (large) scale picture. What’s going on at the regional and/or national level?

- Then start to drill down to your target area. As you zoom in, use models with a finer resolution if you can. You can’t understand the small-scale meteorology without knowing what’s going on at the large scale.

- Look for where the parameters for your desired photography best come together.

Know Which Models to Favor in Your Weather Forecasting

If the models you’re using do not agree, it’s critical to know which ones to favor. You can conduct a quick model evaluation by answering the following questions.

- How have the models performed in recent runs? Have they been accurate?

- How has the model historically performed for the type of weather you wish to include in your landscape photography? Look at its performance over the past 5 years or so.

- Has the model been consistent from run-to-run? Or is it all over the place?

Remember how consistent the GFS was during my analysis of Hurricane Henri? That’s why I favored it so heavily in my forecasts. And in the end, it ended up being correct. In the 48 hours prior to landfall, the other models brought Henri’s projected track as far west as New York City prior to swinging back east. Henri made landfall near Westerly, Rhode Island.

Model Parameters You’ll Commonly Use Weather Forecasting For Landscape Photography

Weather models calculate and output tons of parameters. For landscape photography, there are several that you will routinely use.

- Temperature

- Wind, Height, and Pressure

- Dewpoint and Relative Humidity

- Cloud Cover, given as a percentage

- Predicted Radar

- Precipitable Water (how much water is available in the atmosphere to make precipitation)

- Vorticity and Vertical Velocity (used to determine if cloud cover is increasing or decreasing)

We’ll cover parameters specific to severe, fire, and winter weather in a future tutorial.

Quick Overview of Weather Forecasting Parameters in Landscape Photography

In landscape photography, you’ll find that you have a core set of parameters that you routinely use. Here are some of the most common ones.

| Weather Phenomenon | Optimal Conditions |

|---|---|

| Sunrises and Sunsets | Moderate (30-50%) Mid to Upper-Level Cloud Cover Best in late fall/early winter Be aware of the potential for increasing or decreasing cloud cover |

| Astrophotography | Clear Skies (0% cloud cover) Low Relative Humidity Calm Winds Cold Temperatures As Close to a New Moon as Possible |

| Golden Hour | Minimal (less than 30%) Cloud Cover Best sun angles and warm colors in summer |

| Misty Forests | Cool or Cold Temperatures High, but Less Than 100% Relative Humidity Dewpoint should be a few degrees below the temperature Calm Winds |

| Post-Snowstorm Winter Scene | Cold Temperatures Clearing Skies Minimal Wind Low to Medium Relative Humidity |

Next Steps

Now that you’ve been introduced to the models, the next step is to dive into how to use them. In the next tutorial, we’ll expand on the last section. You’ll learn what each weather forecasting parameter is as well as how to apply it to landscape photography. If you have any questions, please leave them in the comments below or email them to me directly. I look forward to seeing you in our next tutorial.

Top Photo: Beautiful Fall Cape Cod Sunset

Woods Hole, Massachusetts – October, 2021